The Lock and the Key: An Anecdote on Alisher Navoiy’s Self-Mastery

This anecdote, preserved in a sixteenth-century court memoir, offers a revealing glimpse into how Alisher Navoiy (1441–1501) was understood by his contemporaries in matters of personal life and moral conduct. Far from a tale of scandal, it is a moral narrative shaped by the values of its time, presenting Navoiy not as a man devoid of desire, but as one who consciously mastered it. Read today, the story illuminates the ethical ideals, literary conventions, and courtly curiosity that surrounded one of Central Asia’s greatest cultural figures.

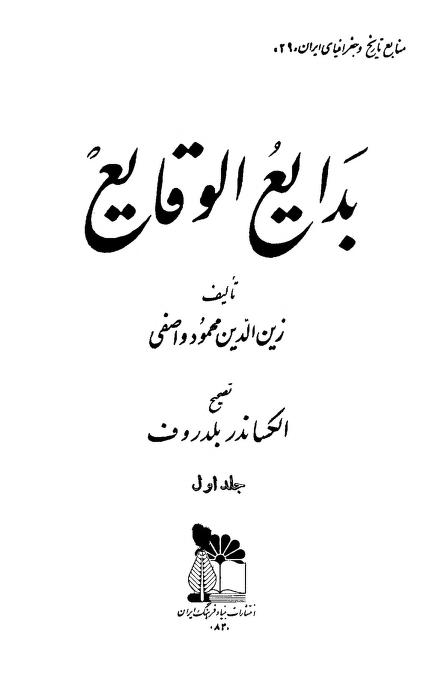

The following passage is quoted from Badāyiʿ al-Waqāyiʿ (begun in 1517) by Zayn al-Din Wasifi, presented here in English translation based primarily on Muhammad Rizo Ogahiy’s Chagatai Turkic rendition, with modern Uzbek refinement and reference to the Persian original.

*****

Alisher Navoiy never married, a circumstance that aroused quiet astonishment both in public life and within the private circles of his age. Sultan Husayn Mirzo explained this by Navoiy’s chastity and freedom from sensual attachment, believing his heart to be wholly devoted to learning and poetry.

The sultan’s beloved wife, Khadija Begum, however, held a different view. “If this is so,” she remarked, “then the truth of the matter must be put to the test.”

Accordingly, she dispatched one of her most beautiful concubines, Davlatbakht—renowned in her time for her unrivaled skill in charm and flirtation—to Navoiy’s house, instructing her beforehand in various stratagems.

Davlatbakht arrived at Navoiy’s residence at the hour of the evening prayer. By various pretexts she engaged him in conversation, lingering until darkness had fully settled. At last, she cast a questioning glance at Navoiy—a glance that silently asked whether she might remain there for the night.

Perceiving her unspoken request, Navoiy answered calmly, “There is no difficulty. Stay here tonight.”

He arranged lodging for her in a chamber adjoining the house. After a short while, the concubine returned and entered Navoiy’s room. At once, Navoiy perceived her intention with clear insight, yet deliberately chose to feign ignorance.

In a gentle, deliberate voice the concubine said, “Sir, it is as though every hair upon my body has turned into a chain, drawing me irresistibly to this place. Perhaps this boldness is born of the hope that you have once cast a gracious glance upon your humble servant.”

Navoiy replied, “Such flattery and such proposals are of no use. It is now evident for what purpose you have come. Between you and many others there exists a difficult matter—a lock whose resolution has long been delayed. Now, I shall show you its key.”

He then took the concubine’s hand and placed it upon his knee, guiding it lower, until it rested where his manhood stood firm and unmistakably awakened. “Know this,” he said, “this is the “key” that is fully capable of opening that lock. I possess the power to act. Yet I did not act in the past, I do not act now, and I shall not act in the future.”

Then he recited:

To turn away from lust is lasting gain;

To bow to craving marks a moral stain.

When this account reached the ears of Sultan Husayn Mirzo and Khadija Begum, the sultan’s conviction was confirmed, and Khadija Begum’s esteem for Navoiy increased many times over.

*****

Explanatory Notes

- Nature of the source

Badāyiʿ al-Waqāyiʿ is a tazkira–memoir rather than a modern historical chronicle. Works of this genre combine personal recollection, court anecdote, and moral illustration. The episode should therefore be read as a didactic narrative, not as a strictly verifiable biographical record. - Purpose of the anecdote

The story addresses contemporary speculation regarding Navoiy’s lifelong celibacy. By demonstrating his physical potency while emphasizing deliberate restraint, the anecdote seeks to refute any suggestion of impotence and instead affirm moral self-mastery. - Potency and restraint

In the cultural logic of the time, virtue was not defined by the absence of desire, but by dominion over it. The episode underscores that Navoiy’s abstinence was a conscious ethical choice rather than a physical incapacity. - Symbolic language and gesture

The metaphor of the “lock” and “key,” together with the deliberate yet restrained gesture, reflects the conventions of elite Persianate literary culture, as expressed in Navoiy’s Chagatai Turkic prose, where indirection preserved both meaning and propriety. - Historical caution

Modern scholars treat this narrative as illustrative rather than factual. It reveals how Navoiy’s moral reputation was understood, defended, and amplified within later literary tradition, particularly in response to courtly rumor and curiosity. - Love and renunciation in Navoiy’s poetry

In some of his poetic works, Navoiy alludes—indirectly and within conventional literary tropes—to the experience of love and emotional attachment. Later readers have sometimes interpreted these hints as suggesting an early beloved and a subsequent turn away from marriage. Such readings, however, belong to the realm of literary self-representation rather than verifiable biography. In the ethical worldview reflected in Navoiy’s writings, renunciation is not the denial of feeling, but the conscious redirection of personal desire toward poetry, moral refinement, service to humanity, and good deeds.

###

Prepared by Azam Abidov (A’zam Obid)